The Lama? What?

This is an approximate script (with errors) of the Double Dorje podcast at the Double Dorje podcast

Hello, and let me begin by extending a very warm welcome to the Double Dorje podcast. And now…

I bow down to the Lama. A lot of Buddhist texts, liturgies and philosophical discourses, start with those words or something very similar. Instead of the lama it might be Buddha, it might be Vajrasattva, it might be the three jewels or the three roots. But the fact that it is often the lama shows just how important the lama is in Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism has even been called Lamaism. The history of that term is rather interesting. It was probably invented by, and was certainly popularised by, Lawrence Waddell, whose book, entitled “The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism”, was one of the first sources to tell the white Western world anything about the Buddhism of Tibet. It was published in 1895, making it about 130 years old. He was something of an explorer and acquired quite a few military medals in the course of his career, writing about Tibet, Assyria and the history of civilisation. His literary output, for all his titles and professorships, and for all that he was the cultural consultant to Younghusband’s invasion of Tibet in 1904, was not received at all well by the academic world. His “Lamaism” book did indeed contain quite a lot of factual information, information that was particularly interesting because it was introduced into a near-total vacuum of knowledge about the Tibetan styles of Buddhism, and perhaps in part for that reason seems to have caught the public imagination to some extent. It was, however, a prejudiced expression of the white European sense of superiority. I once borrowed a copy from a library, so I can firmly second this opinion. His Wikipedia entry points out that these days it would be called an example of “Orientalism”. If you don’t follow this aspect of cultural studies, you might mistake that term for simply implying that some material – writing, painting, whatever – shows an interest in matters Oriental, but it has in fact acquired a rather special meaning. To borrow again from Wikipedia, it is “a general patronizing Western attitude towards Middle Eastern, Asian, and North African societies”, thinking of them as curiously interesting, static and underdeveloped. In any event, Waddell’s work has been seen as a prime example of this kind of dismissive attitude.

So, in short, we don’t use the word “Lamaism” anymore.

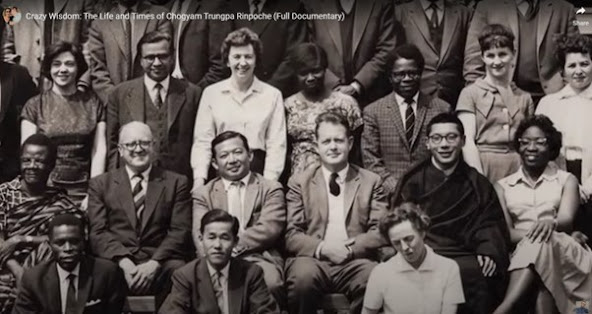

Or do we? Probably not, but here’s something I remember from the mid-70s, by which time Waddell’s term of Lamaism had decades earlier been recognised as being at best in poor taste. My first lama was from the Kagyu school. He had been brought up and educated in Tibet, and had been expected to play an important role in his monastery in eastern Tibet. The Chinese invasion put the kibosh on that, as on so many other things, and he was forced to flee at around about the same time as the Dalai Lama left for India. At the time I’m remembering here, he would occasionally give an after-tea talk in the tearoom of what was then called Kham Tibetan House. Nowadays it is known as Marpa House, the change in name being due in part, I was told, to the way people would think that the name was “Calm Tibetan House”. Not helped by the secretary’s voice on the answering machine as she told callers that “We are in meditation right now and cannot come to the phone.”

Anyway, I recall him saying on one of those occasions how he thought that perhaps Lamaism wasn’t such a bad word after all, because of the importance of the lama in the liturgy and practice of Tibetan Buddhism. But that view has not gone mainstream!

So let’s look at the word a bit more closely. It is the Tibetan translation of the Indian word guru, and literally just means high one or highest. I hear that in its Indian origins, “guru” initially simply meant “heavy” – your guru was your heavy dude! For all practical purposes, guru is now an English word, and it does carry a lot of baggage with it, so many translators out of Tibetan will prefer to use lama rather than guru. Attempts have been made to find an English equivalent such as teacher, or spiritual master, but these run the risk of obscuring the fact that, in Tibetan, lama is a very, very multilayered word, with a number of meanings that come into play all at once, but with a weighting that depends on the context.

Somewhere, I clearly remember, there is a text with a traditional list of the most important meanings of the word lama, but for the life of me I can’t find it, either in my own library or on the net. So if anybody is actually listening to this, and knows what I’m talking about, please use the comments and let us know! The gist of it, however, is that the lama appears in many forms. He or she can be a person, indeed including the teacher in front of you. The lama can refer to the head honcho of one or other of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The lama can be in the form of the teachings, as texts, or can appear as the yidam, which is the form of the Buddha that a practitioner takes as the focus of their meditation and devotion. The lama can be the dharmakaya, another complex term. For the moment we can take it, at the risk of being over-simple, as the true body of the Buddha, beyond particular forms. It can also be the true nature of one’s own mind.

When a practitioner starts to engage seriously with one or another of the schools or traditions of Tibetan Buddhism they are likely to start to use liturgies and visualisations involving what is known as the refuge tree. The concept of going for refuge is common to pretty much all forms of Buddhism, and I expect to talk about that in another episode, but I’m talking here about the way it is used in the Tibetan traditions. The practitioner visualises a magnificent tree growing in the middle of a beautiful, clear and fragrant mountain lake, and the sources of refuge are arranged on the branches of the tree. There are Buddhas, there are texts full of teachings, sutras and shastras, there are deities and bodhisattvas. I won’t go into more detail because those details depend very much on the particular tradition in which the student is practising. In the centre of this tree, the largest figure in a painting of the tree, is the lama. The form of the lama here, however, varies. In some traditions the form used is that of a golden Buddha, much as you might imagine it. In the Nyingma tradition the lama will often appear as one of the forms of Guru Rinpoche. You may hear people referring to him as Padma Sambhava. For practitioners and followers of the Nyingma school, Guru Rinpoche is looked on as a “second Buddha” of this age.

The point here is that Buddhas cannot liberate us from the cycle of suffering. They would if they could, but since the cycle is caused by our own, beginningless confusion and mental poison, Buddhas can only show the way. The natural expression of the enlightened mind, which cannot help but be compassionate, is therefore to adopt the role of teacher or lama in any way they possibly can.

Elsewhere, the lama may appear as Tsong Khapa, with his pointed yellow hat, founder of the Gelugpa school with which the Dalai Lama is associated. In the Kagyu school, where I first studied, the form used in this position is that of Dorje Chang, the “Holder of the Vajra”, a midnight blue, peacefully smiling Buddha, seated cross-legged and dressed in the silks of an Indian prince. The reasons for that form would be outside the scope of this episode, but we should note that that is the form in which we visualise our own, personal, human guru. It is also the form visualised at the very top of the tree representing the Buddha as the teacher of the methods of tantra and mantra, from whom all the teachers of the lineage originate, shown one by one, arranged in the tree coming down to one’s personal teacher. In this case, the point is that one’s personal teacher is the lama because he or she expresses or embodies the blessing and transmission of the lineage.

I used to know quite a number of students of the great Tsultrim Gyatso Rinpoche. From one of these I heard a story about another one of them, who will – of course – remain nameless. It appears that this student, being very devoted to Tsultrim Gyatso, was doing the meditations involving this refuge tree. In this context, that meant working to accumulate 100,000 full length frustrations – visualising Tsultrim Gyatso’s form as we would conventionally think of it, almost a photograph. The lama, Tsultrim Gyatso, discovered this, and was more than a little displeased, explaining that yes, he was this student’s lama, but that he was only an expression of the refuge because he was the endpoint of the line of blessings, inspiration and realisation originating from Dorje Chang, and it was Dorje Chang who had to be visualised. Otherwise – dud blessing.

Now that I’ve tried to give a bit of a hint at both the complexity and the importance of the lama in Tibetan Buddhist practice, it’s probably time to take the bull by the horns and look at the dark side. It doesn’t take a lot of thought to see that this reverence for and obedience to the guru, which is part of the spiritual method as well as being ingrained in Tibetan culture, is a wide-open gateway for abuse. Another factor we should be aware of is the extreme reluctance of Tibetans to criticise others, in particular when those others are perceived as perhaps having a higher social or religious status. It is almost physically painful for them! The result – inevitably – is a code of silence of the type we know so well from the poor Catholic Church all the way through to the entertainment industry. Everything changes, and the Tibetan religious world is slowly getting used to the fact that we modern people will not accept attempts to stonewall criticism of figures, when we know damned well that they are lying about their experience and qualifications while using their apparent high position to abuse students sexually and financially. But the change is frustratingly slow.

I, too, I’m not going to name names here, because it easily results in bitterness. Some of the lamas in question amazingly still have committed followings, so if you are going to say that so-and-so is a sexual abuser whose teachings are flimsy nonsense with little basis in actual Buddhism, you had better, on the one hand, be prepared with your facts, but you had also better be prepared to make little or no progress after the bitterness. If you are interested, it is easy enough to search the net for something like Tibetan Buddhist lamas scandal USA France and take it from there, but be warned: not only is the material you will find unsavoury, but that very fact has been massively exploited by pro-Chinese, anti-Tibetan organisations. A good slice of what you will find through those searches is heavily slanted anti-Tibetan propaganda containing its own share of lies and willful misrepresentation, sometimes quite absurd.

In a traditional context, what can we make of Naropa? I am not talking here about the educational institution in Colorado deriving from Trungpa’s activity in America, and itself the subject of serious allegations. That could easily be the first thing that comes up when you search. I’m talking about the famous Naropa who is a major figure in the early Kagyu and other lineages. His story is sometimes used to encourage, or at least eulogize, blind obedience. Tilopa, his teacher, is said to have subjected him to 12 trials over the course of 12 years, including jumping off the roof of a temple and breaking all the bones of his body before finally introducing realisation in Naropa by slapping him with his sandal. I don’t think it requires huge sophistication to realise that the story is to a large extent a fairytale. Perhaps it is a deep, meaningful fairytale encouraging inspiration and confidence in the lineage, but it remains a fairytale. Taken as factually true, it has been used to justify very bad behaviour.

Much the same might be said of the story of Marpa and the way he made Milarepa repeatedly build and demolish a tower with his bare hands. (I just remind you here that I will include in the description a list of some of the names and terms you might like to look up.) Anyway, we now know that many of the layers in the story of Milarepa are only found in later versions of the life story. Inspiring, it is. A good read, it is. Full of poetry and inspiration, it is. But it is a novel, even though based in some kind of reality. The details of these stories, however, would take us too far away from the point of this particular episode, which is to think about the general way in which the lama is conceived.

I think it’s important to face up to these problems, especially for any newcomers who might be listening and who might perhaps still carry the hope that Buddhists, and Buddhist teachers in particular, are immune from humanity’s stupid wickedness. Forewarned is forarmed. THAT SAID, another standard social mechanism is at work – self-serving schemers with little or no shame have a way of rising to the top. Look at Donald Trump! There are many, many Buddhist teachers who are wise, compassionate, learned, and experienced. Often they have a low profile, especially when it comes to digital media. To find them you must keep your ear to the ground and follow your nose, if I may mix my metaphors. I have met quite a few over the years – they are there!

To save confusion (imagining that it’s even possible to stop confusion ??) it might be wise to mention the term “root lama”. In some circles people like to run around saying “Oh, my root lama is so-and-so, who is yours?” This can soon lead to the confusion I mentioned and arguments if we are not aware that, quite traditionally, the term “root lama” has different meanings, in different traditions. It can refer to a student’s most important lama, the one they have learned most from and whom they most respect. I have been led to believe that in the Sakya school, anyone from whom student has received a higher empowerment is automatically considered a root lama. If, as can easily happen, a student receives such empowerment from more than one lama, they then have multiple root lamas, which sounds a bit weird to people who don’t know that the term simply is used that way in that context. In the Kagyu school a student may have a close teacher from whom they have learnt a lot, may have received higher initiations from the same lama – or indeed others – but still not feel that they have a “root lama”. In that context, you see, the root lama is the person who first properly introduces the student to the true nature of their mind – and that doesn’t always happen easily! I remind you of the story of Naropa being hit by the sandal, a story which may or may not have happened, but the significance is that at that stage Naropa had studied enormously, practised massively, and held high positions in the Buddhist hierarchy. He was, without question, one of the most advanced students, scholars and practitioners that you could find. But it was only at that moment that he was shocked into recognising the true nature of his mind. Tilopa was then not just his most important lama, but was also now his root lama.

In other systems, the Nyingma, for example, the lama is, in the first place, the one who is the natural expression of the Buddha’s enlightened compassion. Now it is well known, and obvious, that Buddhas simply cannot just liberate sentient beings from suffering, if only because of the simple logic, that if they could, they would. All the same, compassion cannot be separated from enlightenment at all, so they practically have no choice but to take on the rôle of teacher or lama, and to do that in any conceivable way. Or, I suppose, inconceivable.

Much the same mechanisms can be seen in liturgies. Generally speaking the lama is visualised as a small form over the head of the great majority of deities. The white 4 armed form of Chenrezi will be seen to have the small, ruby-red figure of Amitabha, the Buddha of Limitless light, just above the top of his head. A visualized form of the Buddha may also have the lama in his or her heart, or the lama may even be in both places.

As an object lesson we can take a look at the Lama’i Naljor (Tibetan) or Guru Yoga. In a Guru Yoga, the practitioner unites his/her mind with that of the lama. It’s the culmination and most important section of the preliminary practices, the ngöndro – to which we shall return! Again it is obvious that while our personal, human (sometimes all-too-human) teacher IS the lama, it’s not as if we share his/her shopping list or fondness for cheese and onion crisps. But we DO share the blessing of the lama’s mind.

Once again, longer sadhanas often have a Lama’i Naljor section in their run-in, and the lama here is likely to take the form of a deity such as Vajrayogini, showing again that the lama goes way beyond the individual human teacher.

So, putting it together: once we have entered the vajra world, the magic circle, the mandala of some form or tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, the lama is in a sense everything: the source of liberating instructions, the expression of the Buddhas, the representative of the great gurus of the lineage, and also one’s personal teacher, the expression of compassion for all beings, inspiring our own compassion, as well as the magical spark in our heart drawing us on to our own realisation of our true nature. That’s why the true nature of the mind TNOTM is the ultimate lama.

Well that’ll do for now! Don’t forget to like, subscribe, share, tell your friends, whatever – and keep up the good work!

Comments

Post a Comment