Ato Rinpoche will be missed. Plus his two eyes.

Below is the approximate script, with possible errors, of the fifth episode in the Double Dorje podcast, released on 28 May 2024 at the Double Dorje podcast.

Hello good people, and a warm welcome again to the Double Dorje podcast.

Through an unusual coincidence, which I’ll get to later, I heard of the sad passing of Ato Rinpoche shortly before the news spread across the Internet. But not all you good listeners will have heard of Ato, so while you can search the Internet, of course, I’ll tell you just a little a bit about him.

He was born in 1933 which, by the way, tells you that he was 91 when he passed the other day. He was recognised as the main tulku, for which the usual gloss is “reincarnate lama”, of his monastery at Ato, not far from Jeykundo, or Yushu as the Chinese call it, in eastern Tibet. When I say “not far”, that is in terms relevant to the time and place. How many days horseride it was, I don’t know. Perhaps a couple? Maybe less, as he did say that they would picnic at a place just outside Jeykundo. He was a nephew of the famous, late Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. I will admit that Tibetan family relationships confuse me from time to time, as the terms don’t always map exactly on to our Western terms, but I have been led to believe that in this case at least he was the nephew as we would understand the word.

For the first years of his life he received the traditional education and training appropriate for his station, and began to fulfil those duties. Then, in his later 20s, the Chinese invasion happened and like so many lamas he was forced to flee.

Ato was not in fact his name. I was told by his wife, Alethea, that when he arrived on the train to the place where Tibetans were assembling, somebody said, “Oh, look, it’s the Rinpoche from Ato!” The name stuck.

In India, he played an important part in running the “Young Lama’s School” that had been set up to educate and train the young tulku’s who had joined in the escape. At some point in those years he met Alethea who was I think (though I could easily be wrong here) working there in some kind of missionary capacity. And then – love happened! Ato was always very correct about his doings, and at that time was, of course, a monk. Something had to be done! He would relate later how scared he had been going to see the 16th Karmapa to get permission to “give back his robes”. Permission was, however, granted, and in due course he and Alethea married and moved to England.

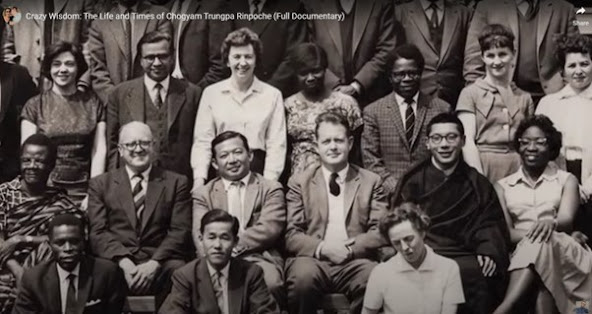

Three other lamas, namely Trungpa who was later to become notorious and move to America, Akong Rinpoche, who looked after Samye Ling for many years and Chime Rinpoche, my own first teacher, were all more or less “sent” to the UK with the idea of acquiring some knowledge of the Western world and taking it back for the benefit of the Tibetans who had just lost their very traditional, closed, homeland. Ato was therefore not one of those, having arrived for quite a different reason, and it is the best of my knowledge just a coincidence that Chime Rinpoche, who was also a nephew of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, founded his meditation centre in a village only about 15 miles from where Ato lived in Cambridge.

He did have a few Western students, but worked for some years as a hospital porter, oddly enough somewhat similar to what Akong Rinpoche did in Scotland. In the course of that work his back was injured, and from that time on he received a disability pension. Bad for him, but great for students, as it gave him more time to look after his regular teaching group in Cambridge as well as to travel, teaching in many places around the world, which is how I came to see him in Hamburg where I was living, in Hanover, in Schleswig Holstein (which is the bit of Germany that sticks up and has Denmark on the end), as well as at a centre on the Beara Peninsula in West Cork, Ireland.

I had come across him in earlier years, but it was not until the early 90s that I began to take a number of teachings from him, starting at that centre, Storchenhof in rural Schleswig Holstein. You could translate Storchenhof as “Stork Farm”, and there really was a stork’s nest in use at the top of a pole in the centre of the yard. This was where something quite remarkable happened. Well, remarkable to me, anyway, though I suppose to the outsider it was almost trivial little incident. However it was the start of a stronger connection with him and a period of time when he was my most important teacher.

To explain the significance, we have to go back 16 years earlier when I had been one of a few students of my first teacher, Chime Rinpoche, who were lucky enough to receive a Vajrayogini empowerment from the 16th Karmapa. Those were the days, eh, when that could happen to a raw and floundering little student like myself! By that stage I had got quite a long way through a first round of the preliminaries, but I hadn’t finished. It was clear that this empowerment was a preparation for the future, and there appeared to be no expectation of starting the practice at that stage. And there it remained for years, treasured but unused.

So now, back to Storchenhof in the early 90s. Ato Rinpoche had taught there the previous year, which had been the first time I had received teachings from him, but this time his teachings were extending over nearly a full week. Toward the end of one of the morning sessions I had asked a question – I can’t remember what – and after giving an answer he looked at me and told me to come and see him after lunch. What was that about?

When I entered his room that afternoon he said that something had told him that he should give me the textual transmission for the short daily practice of Vajrayogini. “Well,” I thought, “golly gosh!” I told him that I had received the empowerment from the Karmapa back then, and he said, “Ah, that explains it. It must be starting to work!” After the reading transmission, he said “Now you really begin-start!” So that was the beginning of a number of years during which he was my main teacher. But that’s more than enough about me.

Even when my practice had moved over for reasons that are part of a completely different story to the Nyingma tradition, I remained in touch with Ato Rinpoche, although at a very low level. In fact not much more than an email every couple of years saying “How are you, hope you and the family are well, we are well here, dot dot dot.” That exchange had not happened for quite a while, probably over a year, but on MondayI of that week I stumbled across a couple of pictures of Sechen Rabjam Rinpoche. “Wait a minute, I know that place,” I thought. “It’s Ato Rinpoche at home!” One picture was of the two of them in his back garden, the other was in his living room, with Alethea and Chime Rinpoche as well. I figured that they would most likely have these pictures, but for better or worse I spend more time browsing around the Internet than I imagine Alethea does, so I took copies of the pictures and sent them to her (she manages Rinpoche’s communications), just in case. An hour later an email came back from her, containing the sad news that he had passed away, peacefully at home, thank goodness, on the Saturday before. A strange little coincidence. By the end of the day the news seemed to be out on the Internet.

So all that was really just to offer a few memories of somebody who will be missed. I had planned to make an episode about Ato’s “two eyes” in a few weeks time, but in the light of the above this is the time to make the point.

Many times Ato would teach from the songs of Milarepa. These are popular amongst all Tibetan Buddhists, but have a particularly strong connection to the Kagyu. The other book that he would often teach from was the Words of My Precious Teacher by Patrul Rinpoche. Much of the material in that book would fit perfectly in Kagyu teachings, but there are details that make it a very Nyingma work. He would say that these were his “two eyes”.

Those of you who are familiar with the way Tibetan Buddhists do things, will know that it is very usual to have a “bundle” of loose leaf texts used for regular practice. I recall him saying that when he was in some group practice together with Nyingma people, they might look over his shoulder and say “Oh, I see you are Kagyu!”. If, however, he was amongst Kagyu people, they might look over his shoulder and say “Oh, I see you are Nyingma!”

He was therefore as free from sectarian bias as they come. He knew the difference, but was comfortable with both.

He will be missed.

Okay, that’s it! Don’t forget to like, subscribe, share, tell your friends, whatever – and keep up the good work!

Comments

Post a Comment