Refuge and the Three Jewels

Approximate script, with some variations and possible errors, of the podcast at podbean

Refuge and Bodhicitta – and one simple tune.

Hello dear listeners, and welcome indeed to another episode

of the Double Dorje podcast.

There can’t really be any doubt that saying that taking

refuge is the gateway to Buddhism is a good metaphor. It’s not perhaps quite so

cogent, but does nevertheless probably makes sense, to say that having come

into the entrance hall, adopting the bodhisattvas’ vow and training to develop

bodhicitta is the grand staircase leading up to the great rooms above. And

although, as I keep saying, I’m not trying to give you a course in Buddhism,

having just looked at the four revolting thoughts in the last episode, it does

follow very naturally to look at the next step – taking refuge.

In a moment, we’ll look at that, but first the quick “call to

action” as it’s known. Do, please, take a moment on whatever channel you are

listening, to like this episode, subscribe to this podcast, share it with your

friends or on social media, or indeed whatever else might be appropriate on

your channel. It really does help. Thank you!

So, to the subject of taking refuge. It is the moment where

you take up the practice of Buddhism, and most importantly the orientation

towards that practice. As seems to happen rather often, I feel that before

talking about what taking refuge actually is, it would be good to dispel one or

two misconceptions.

In that sense, let’s start with the question of who it is

that gives refuge, or the refuge vows? In some traditions there are strict

rules about this, but in others it can be anybody who you can trust to be a

representative of Buddhism. This is one of the most important steps you ever

make, so it would clearly be ridiculous to take your refuge vows with the aid

of someone you did not like or respect just because they “technically”

satisfied the rules. But it is a mistake to think that this process turns the

person administering the vows into “your teacher”, “your Lama” or anything of

that sort. Most of all, if Lama XYZ administers the refuge vows to you, it does

not mean that you have taken refuge in Lama XYZ.

This is unlike the situation with empowerments. An

empowerment should create a deep, personal connection between the student or

students and the guru or Lama. Anyway, that’s the case in theory, although

nowadays some empowerments seem to be scattered around like confetti, and even

given “virtually” as online empowerments. Who am I to say that that doesn’t

work? After all, there are, it seems, people who are totally happy with

cybersex, or digital pornography, yet I think most people would recognise that

the real thing is in another league. But that’s an aside. Taking refuge,

however, is not meant to establish a specific connection with the person who

administers the vows, but who really only facilitates the student in taking the

vows, and the connection is with the whole bang shoot – the three Jewels: the

Buddha, the Dharma, the Sangha. In real situations, of course, the student may

indeed have a strong personal connection to the person administering the vows,

it’s just that that’s not essential, and the vows you take is are made to the

Buddha and bodhisattvas, not to a specific teacher or even lineage.

This is what formally makes you a Buddhist. Now you will,

unsurprisingly, find some people taking what quite honestly is a juvenile

attitude to this, saying things like, “why should I identify as anything”, or

“I don’t want to be confined by labels”, or “saying that I am a Buddhist

solidifies my ego”, or other such barren, trivial objections. To these

objections, I say come on, bite the bullet have the guts to accept the label –

actually the honour, the privilege, and the duSure.or would you rather be a neither-here-nor-there

type person?

Did I say vow? Sure. Pride of place does not go to the

question of whether you believe or disbelieve something. It goes to a

deep-seated motivation to do something about the mess we are in, and the

promise to act in ways that will take us in that direction. For details, take a

look at “Dudjom Rinpoche’s “Perfect Conduct – Ascertaining the Three Vows”. You

might know that I typically include a list of technical and other terms that

you might like to look up in the description of the podcast, so you can check

the title of that book there if you want to find it, though I will warn you

that the average reader might find the description of the various vows found in

the Buddhist tradition to be excruciatingly detailed. Perhaps a little more

accessible would be the descriptions given in the Jewel Ornament of Liberation

to which I referred in the previous episode, or to the Words of My Perfect

Teacher, a famous Nyingma text on this and related subjects. All of those

sources will cover these things more deeply and with more authority than I can,

so I limit myself to providing a tasting plate.

First, of course, taking refuge in the Buddha. What does that

mean? On the one hand, the Buddha may simply mean the historical Buddha who

lived two and a half thousand years ago, but is perhaps more often understood

in a broader sense as the three kayas or three bodies of the Buddha. But saying

anything about the three kayas would definitely cause this episode to burst its

banks. In particular, taking refuge in the Buddha means that we shall not to

take refuge in other gods. Traditionally, most Buddhists would take the

existence of some kind of gods, with perhaps some power to help or hinder us,

living on some other plane, for granted. The point is not necessarily to ignore

them, but to recognise that they cannot give us shelter from the shit-storm of

samsara, of the cycle of suffering.

It is precisely around this point that one of the questions

most asked about Buddhism hinges. That is the question of “Is Buddhism a

religion?” I can now give you the true, honest, considered, fair and correct

answer to that question, the answer that will allow you to stop worrying about

this for the rest of your life, namely “yes and no”. Go to any traditional

temple, listen to the chants, enjoy the offerings of lights, flowers, incense

and so forth, and you will have no doubt that Buddhism is a religion. But it

does not include a creator God, with the power to save us, to damn us to

eternal suffering in hell, or just to torture us for a while in Purgatory. So

when the Buddhist teachings advise us not to put other gods above the Buddha,

this is absolutely not in the sense of the claim that the Buddha is the best

God, better than your God, or any other God for that matter. No. It is in the

sense that Buddhism is just not playing that game.

There is something else that follows from this understanding.

In some circles the idea of being a Buddhist Christian or Buddhist Jew is

promoted. Well full marks for openness and generosity of spirit, but not many

marks for clarity. Christianity, if I may make so bold, is founded on the

redemption of sinful humanity through Christ’s sacrifice of his life, so acting

as a proxy for us so that God will not send us to burn in hell, or even just to

oblivion. Buddhism rejects the idea that such a god exists, and rejects the

idea that someone else can save us. The two lines of thought are quite

incompatible, and in my view (feel free to differ) is effectively an insult to

both the Christians and the Buddhists. A quick look at that movement (no, I’m

not an expert in it) suggests that a few exercises, thought of as Buddhist,

such as mindfulness and watching the breath, have been extracted and included

in a prayerful Christian life. Great! It may very well be helpful. But what it

shows is that those practices, popular as they may be in Buddhist circles, are

not definitively Buddhist. It is not in any sense “combining” Buddhism and

Christianity. The two are not playing the same game.

The second of the three Jewels is the Dharma. Scholars will

tell us that Dharma is a very tricky word, with a large number of different,

context-dependent meanings. In the Buddhist context, two are important, and one

of those is in fact quite slippery, being, at the risk of being shot down by

scholars, something like a “true thing”, as in statements such as “all dharmas

are empty of true existence”. Luckily, that’s not the meaning in use here, so

we can put that aspect back in the cupboard. Here, the meaning is very much

that of the Buddha’s teaching. In its simplest sense, that is the words of the

sutras and other such literature. In fact, in visualisations and pictures, the

Dharma may well be represented by a stack of books. Again, it also has a deeper

but closely related sense, which is the deep peace experienced through having

realised the meaning of the teachings. And for a vow related to this jewel? Not

harming. Simple, short, but huge.

The third refuge jewel is the Sangha. If you are now

surprised to hear that this word has different meanings at different levels,

then I obviously haven’t been engaging enough, so I’m sorry if you have fallen

asleep. Most basically, the Sangha is the community of Buddhists, particularly

referring to 5 or more fully ordained monks or, more broadly, of the “bodhisattvas

living on a high level”, which includes popular figures such as the

compassionate Chenrezi, the lovely saviouress Tara, and others.

And what about a specific bit of a vow connected with this?

Not to associate with non-Buddhist extremists. Exactly what is meant here can

be a bit tricky to unravel, but in our hearts most of us know that we can be

hugely influenced by other people. Indeed, making an effort to associate with

other people who are working in the same direction is, in a sense, part of what

taking refuge in the Sangha is about. If, most particularly, we are starting

out on the Buddhist path in a non-Buddhist environment such as a typical modern

environment, our choice of friends can help or hinder progress hugely.

If you understood all the above, then you can in fact take

refuge yourself. It IS valid. But taking it formally is more usual. The

officiating teacher may well take cut a small piece of hair from your head as a

sign that you are cutting the root of the cycle of suffering. You may very well

be given a new name. Some people then use that name in everyday life, but

others find that somewhat pretentious, and prefer to keep their new name in

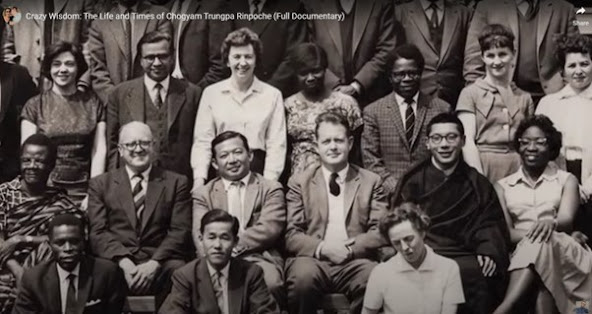

their heart. The ceremony can be very moving. Picture the end of a week of

Buddhist teachings, where some of the newcomers ask in the course of the last

session, whether they can formally take refuge. Those of us who have been

around for longer may well find it very touching as we watch them going up one

by one, having the bit of hair cut and being given the slip of paper with their

new name, as we wish a good journey to our new fellow travellers.

This kind of formal refuge is sometimes made a prerequisite

for other teachings, but in many cases it is just assumed when, for example,

the Chenrezi empowerment is given, that the recipients will have taken refuge,

or at least they will recite a refuge formula early on in the ceremony.

Nevertheless, taking refuge formally and properly with a teacher for whom you

have real respect is a magic moment.

Taking the bodhisattva vow really is a second step. When done

through a formal ceremony, it may happen quite some time after the refuge

ceremony, on a separate occasion altogether.

There is a huge amount of teaching surrounding bodhicitta, in

its relative and absolute versions and so on. The gist of it is not simply to

escape from the cycle of suffering for ourselves, but taking the bodhisattvas vow

means that we will wait and suffer and work until all beings are liberated.

That’s a pretty mighty vow! One very popular text that deals with this is the Bodhicaryāvatāra,

of which it is not hard to find translations. I recall seeing Dalai lama, when

he was teaching in France in the early naughties, actually in tears as he

taught from this text. Having taken this vow, one is a bodhisattva, at least in

training.

Although these two – refuge and the bodhisattva vow – are separate

things, and formally taking up these trainings can be separated by significant

time, in liturgical practice they are often – very often, in fact – put

together as a pair. Here is what, at a guess, might be the most popular verse

for doing this. (I will put this in the description). First, a translation:

Until enlightenment I go for refuge to the Buddha, the Dharma

and the supreme assembly.

By my practice of giving and other perfections,

May I attain Enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings.

So you see the reference to both vows quite clearly.

And this is how you are likely to hear it at a Tibetan

Buddhist centre. With any luck it will be sung more beautifully than what I’m

about to do!

Sang gya cho dang tshog kyi chog nam la

Jang chub bar du dag ni kyab su chi

Dag gi jin sog gyi pai so nam gyi

Dro la pan chir sang gye drub par shog

I’ll put a phonetic version in the description.

So that’s it for today. Just a quick reminder to like share

or subscribe – and whatever promise you have made – do keep it!

Words or phrases you might want to look up:

●

Refuge (Buddhist)

●

Dharma

●

Sangha

●

Three Jewels

●

Bodhisattva

●

Bodhicitta

●

Perfect

Conduct – Ascertaining the Three Vows (by Dudjom Rinpoche)

●

Jewel

Ornament of Liberation

●

Words

of My Perfect Teacher

●

Three

kayas

●

Sutras

●

Bodhicaryāvatāra

And the verse:

Sang gya cho dang tshog kyi chog nam la

Jang chub bar du dag ni kyab su chi

Dag gi jin sog gyi pai so nam gyi

Dro la pan chir sang gye drub par shog

#Buddhism #Vajrayana #Tibet #DoubleDorje #tantra #mahamudra

#dzogchen #lama #mantra #meditation #nyingma #kagyu #Refuge #Bodhicitta

Comments

Post a Comment